Groupies

Groupies

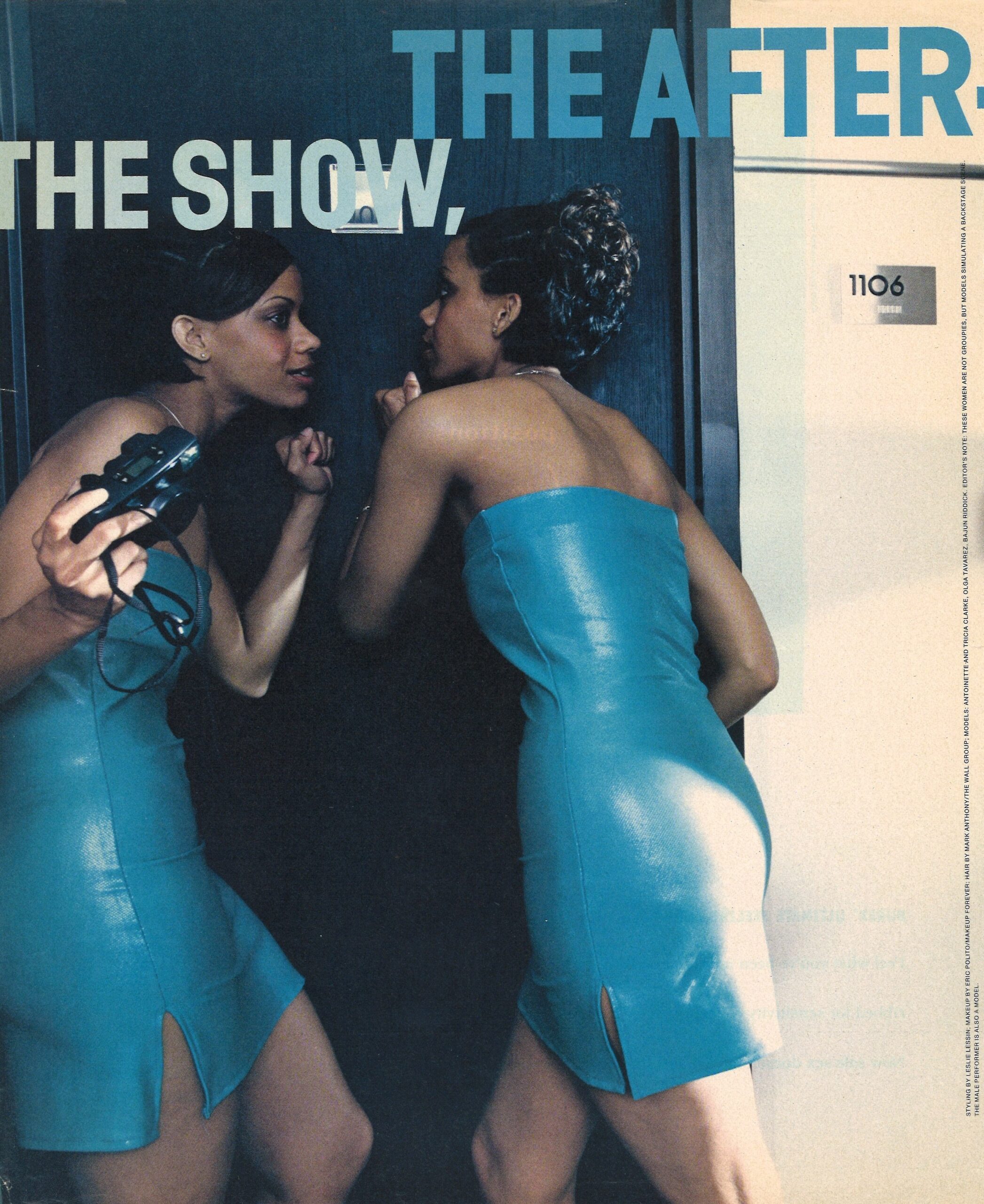

“The Show, The Afterparty, The Hotel: She is the stuff of urban legend. She is a true believer, a pleasure seeker. She is the one crying out to be chosen. She is a hip hop groupie. Will you still love her tomorrow?”

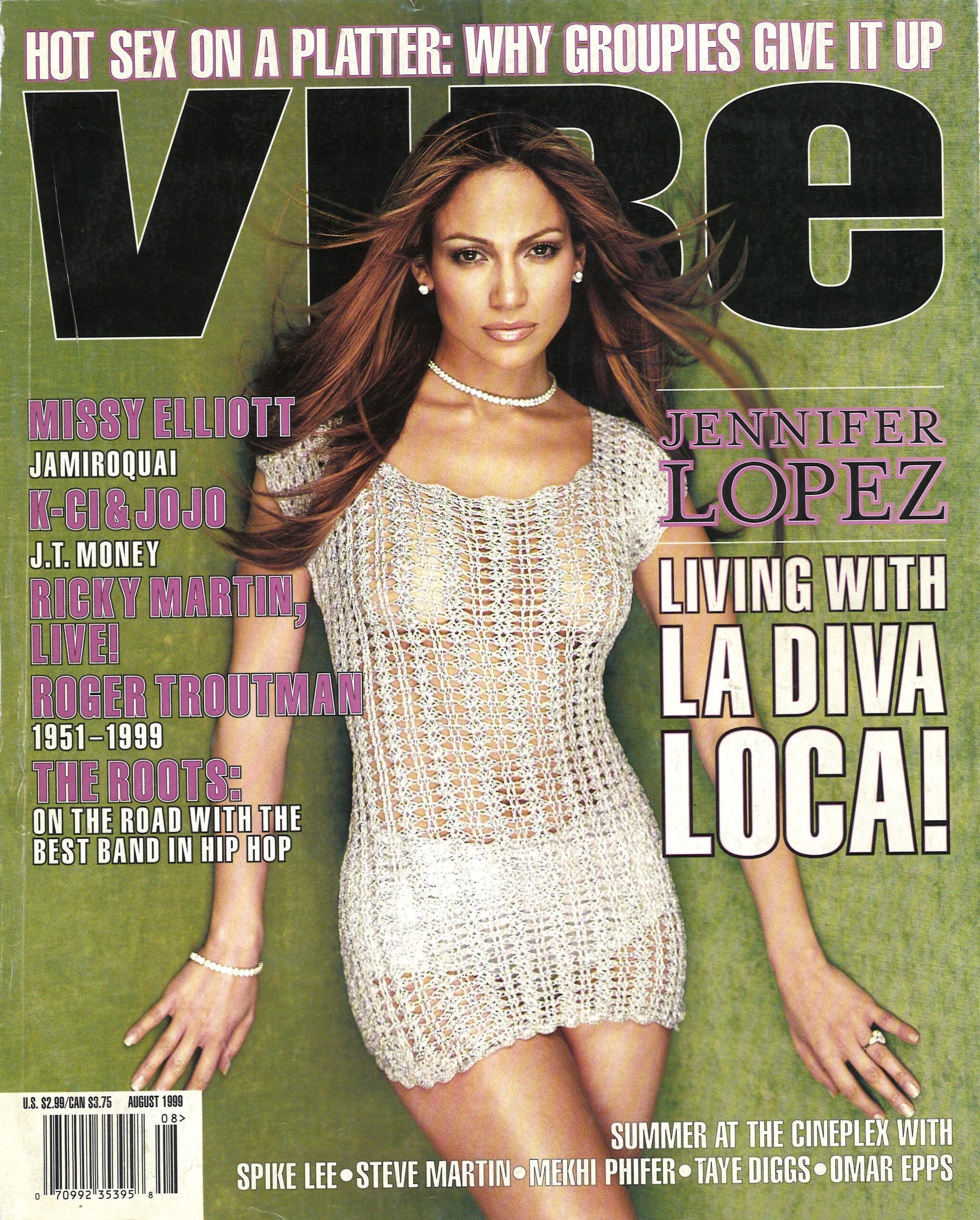

Vibe Magazine

Karen R. Good.

August 1999

Round a table in the barroom of the Sheraton Hotel overlooking the Elizabeth River in Virginia Beach, Va., Jay-Z and his brethren Ty Ty, Radolfo, Hip Hop, Ja Rule, and Memphis Bleek congregate. Ponies runneth over with Hennessey VSOP, glasses rise, and then, a toast:

“This right here,” says Jay-Z soberly, “is for success.”

“For success!” his consorts follow.

“Can’t have success without…loyalty,” Jay continues.

“Yeh, yeh!” they respond.

It’s Labor Day weekend 1998, the weekend during which thousands of students from surrounding Chesapeake Bay communities and black colleges like Howard and Morgan State (and even more southern campuses like Hampton and Norfolk State) come for one last hurrah before school begins.

Jay-Z, who will perform the next night, Saturday, with DMX at the Hampton Convention Center, lifts another glass. “This one here…” he says, quiet now, “this one is for family.”

“One love! Roc-A-Fella fa life.”

“And this one right here is for the groupies!”

Tonight, stories flow like Jesus wine. Tales about tours and one-ups on who’s slept with the most women—groupies, they call them—while on the road, bragging rites as necessary and orgasmic as the act itself. “I’ve fucked half the bitches in the USA,” one maintains. “Half!” Grand, mythic, ridiculous accounts are told of women trailing them from state to state like the feds, of women dared to do things like stand on their heads, of women lining up in twos and threes to suck the same guy.

“Detroit,” Jay-Z promises, “got the best pussy. They just straight ’bout it. I respect that more than somebody who tries to front. I’m in town one night. What the fuck I need with a girl with value?”

With hip hop generating billions of dollars a year—edging out rock as the lifestyle of the rich and famous—tales of young-girl groupies who haunt productions like the Hard Knock Life tour and the Puff Daddy and the Family tour have become the stuff of urban legend. Did you hear about the two Italian chicks on Survival of the Illest? Ultimate groupies. In every city they did at least 20 niggas apiece! A general rule: The fan might accompany an artist to the hotel room to hang out—but the groupie will hit the artist off.

According to Webster’s dictionary term “groupie” originated in 1967 and is defined as “a fan of a rock group who usually follows the group around on concert tours.” Rock fan/girlfriend Pamela Des Barres wrote a book about it called I’m With the Band: Confessions of a Groupie (William Morrow, 1987). Des Barres, who stood on stage in the 1970s while the Who played “Tommy” and traveled with Led Zeppelin as Jimmy Page’s girl, writes that “groupie” started out as a “negative finger-pointing…by someone who obviously couldn’t get backstage.”

Be it rock or hip hop, the magic of music is that it has always inspired certain glory and power. Who among us has not been brought to tears, ecstasy, or uprising by song? But some can’t separate the music from the messenger, and to listen is not enough. Like Des Barres, a hip hop groupie believes in going behind the music in search of real-life fantasy. The artist creates the illusion; the groupie is the true believer.

We must remember, however, that this is a relationship, a compromise. An indulgence of egos in need of satiation and acknowledgement. If that were not so, then Joe Rapper, who’s well-known and married, wouldn’t be standing outside of the Sheraton this warm night, shortly before the football game, passing around a camera showing videotape of a young girl doing him. She is smiling, has pretty eyes, her expression a bit geisha. All you see of Joe are his knees and toes. See this and you understand that man has needs: voyeurism, bravado, and carnality. Woman has similar needs, but add to that a lust for challenge and desire to be chosen. Groupies make sure these needs get met.

On Saturday night there are no post-concert parties worth stopping by, so a few hundred people stand loosely on Waterside Avenue, in front of the Sheraton.

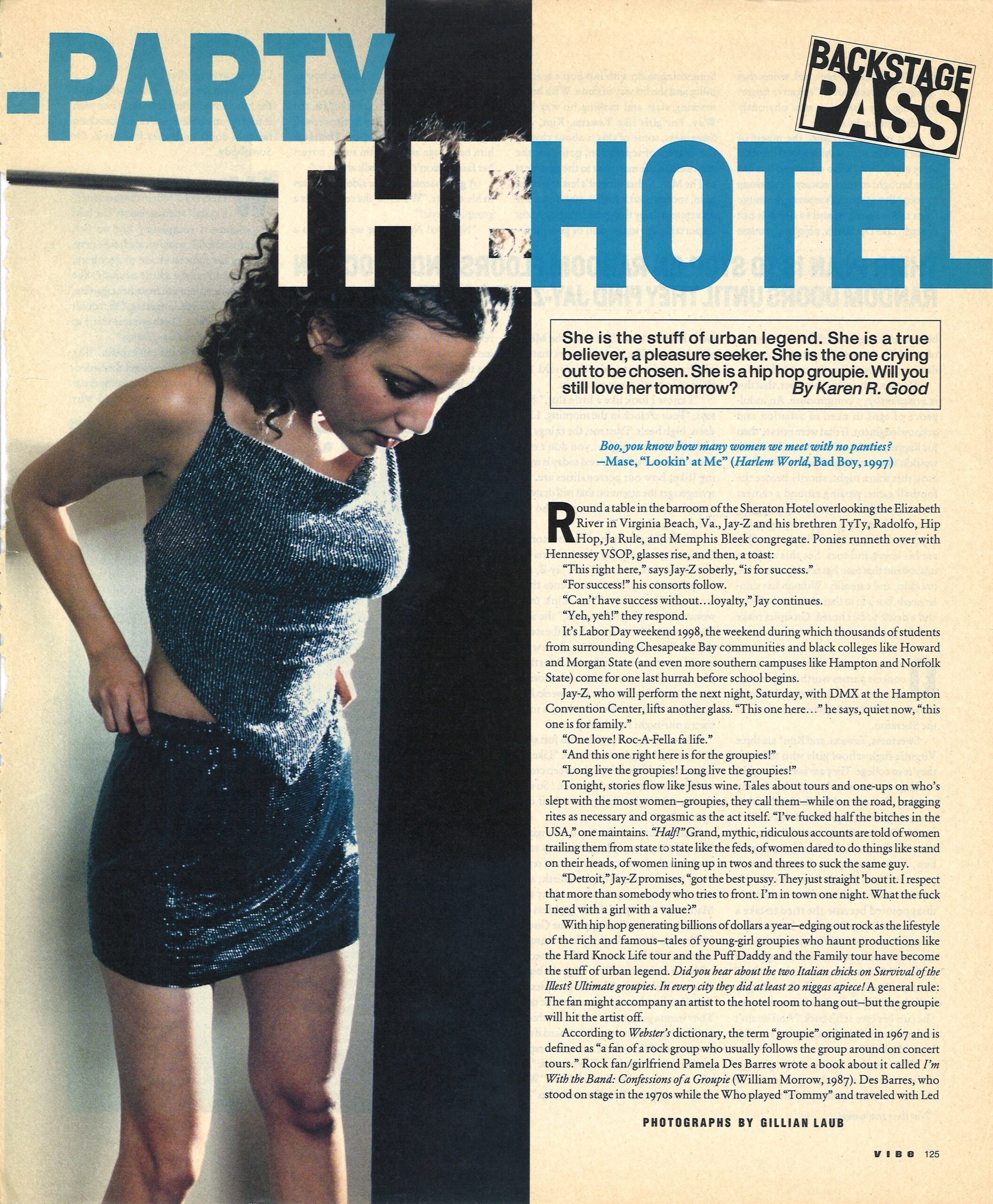

Sweetness, Tawana, and Kim* are three Virginia high school girls who tell boys they’re in college. They are sweet, fass girls, looking to see who’s out this balmy evening. Tawana is thin—the kind of thing country girls call “po”—and wears thick stacked shoes and a micromini. Sweetness, who has dimples and a braided ponytail bun, is thick, sporting second-skins to prove it. Kim, a dark-skinned girl who doesn’t seem to know her beauty, is disappointed because she tried to take a picture with Jay-Z and he hurried her along, despite her outfit—again, a micromini and heels—which she thought was perfect. “It’s about the women he prefers,” she says. As she speaks, a shadow of a guy walks by swiftly and palms Sweetness’s ass. She cuts her eyes at his back. “And he ain’t no damn body.” Her hand rests on her wide hips. “Nobody.”

What makes a hip hop groupie different from any other groupie is the difference in the music and culture itself. Something to do with hip hop’s accessibility and the brevity of fame. With being working class and making no way The way. For girls like Tawana, Kim, and Sweetness, some of this is about closing the degrees of separation, going for the man next to the man next to the man next to The Man. Other times it’s less about the man, more about what manifests: the success and shiny things and, perhaps most important, the suggestion of godliness—God: Rakim, Allah, Nas (“like the Messiah”), Jayhova. The groupie knows that she has limited access to this otherworld. Her skills of seduction can get her in.

“I know I look like a little slut,” Kim says. “Four o’clock in the morning. Little dress, high heels. Trust me, the things I’ve had said to me tonight…you don’t even know. The way we’re dressed today is nothing [like] how our personalities are. I’m trying to get the attention that will draw the attention to him. That’s the girl who will fit his image.”

Chaka Pilgrim, one of the creators of Fanfamily, a company that answers fan mail for artists such as DMX, Jay-Z, and Foxy Brown, says that sometimes these women have a plan. “You think these women are playing themselves,” she says, “but then you’ll see them behind the scenes and you’ll be like, ‘Okay, I was there when we did the concert at the Tunnel. I was there when this bitch came and stuck her tongue in your ear. Okay, here it is three weeks later and she’s in the studio.’ So there’s more than a one-night stand going on.

“Then you get the girls who just want to have sex,” Pilgrim continues. “Like, no panties, grab his hand, put between crotch and ‘Feel my furry wonder-pouch.’ So with that in mind, girls really have their own agenda.”

Male groupies are harder to distinguish. Usually they simply linger and try to be cool, but they also cry real tears of regret every time Lauryn Hill gives birth; they offer Lil’ Kim money to have sex; they stalk Madonna. Shotgun funk goddess Joi (who’s married to Big Gipp of the Goodie MOB) says that male groupies are usually awestruck. “Most times they’re respectful of the art and realize, ‘This might be bigger than me,’ ” she says. “Female groupies, on the other hand, are going to test the men. They wanna get up and touch something.”

That said, when the girls are asked if they have or would ever have sex with a rapper just because of who he is, Tawana says: “Uh-uh.” Sweetness: “Fuck, no.” Kim: “Well, Nas,” she admits, “Nas Escobar. Yep.”

This is Kim’s fantasy: “Aiight, boom: I’m at this concert, right? And I’m in the crowd, in the front. And then it be Nas, the whole Firm on stage. I’m in the crowd, right, and Nas pulls me up there. Then I see him backstage and…” Kim stops, covers her face. “I don’t wanna talk about it.”

A guy listening on the sidelines tosses in his 2 cents. “We know the rest! This is a groupie movie!”

“No! No! No, ‘cause we carry on a relationship!” Kim is adamant. “He takes me on tour and everything, and I’m living the lifestyle he rappin’ about. Look, I love him. I really do. I’m not tryin’ to be funny. I really have a thing for Nas. Unlike anybody else.”

As dawn nears, the girls scurry inside the hotel toward the elevators. Their plan is to stop on random floors and knock on random doors until they find Jay-Z. Or Somebody.

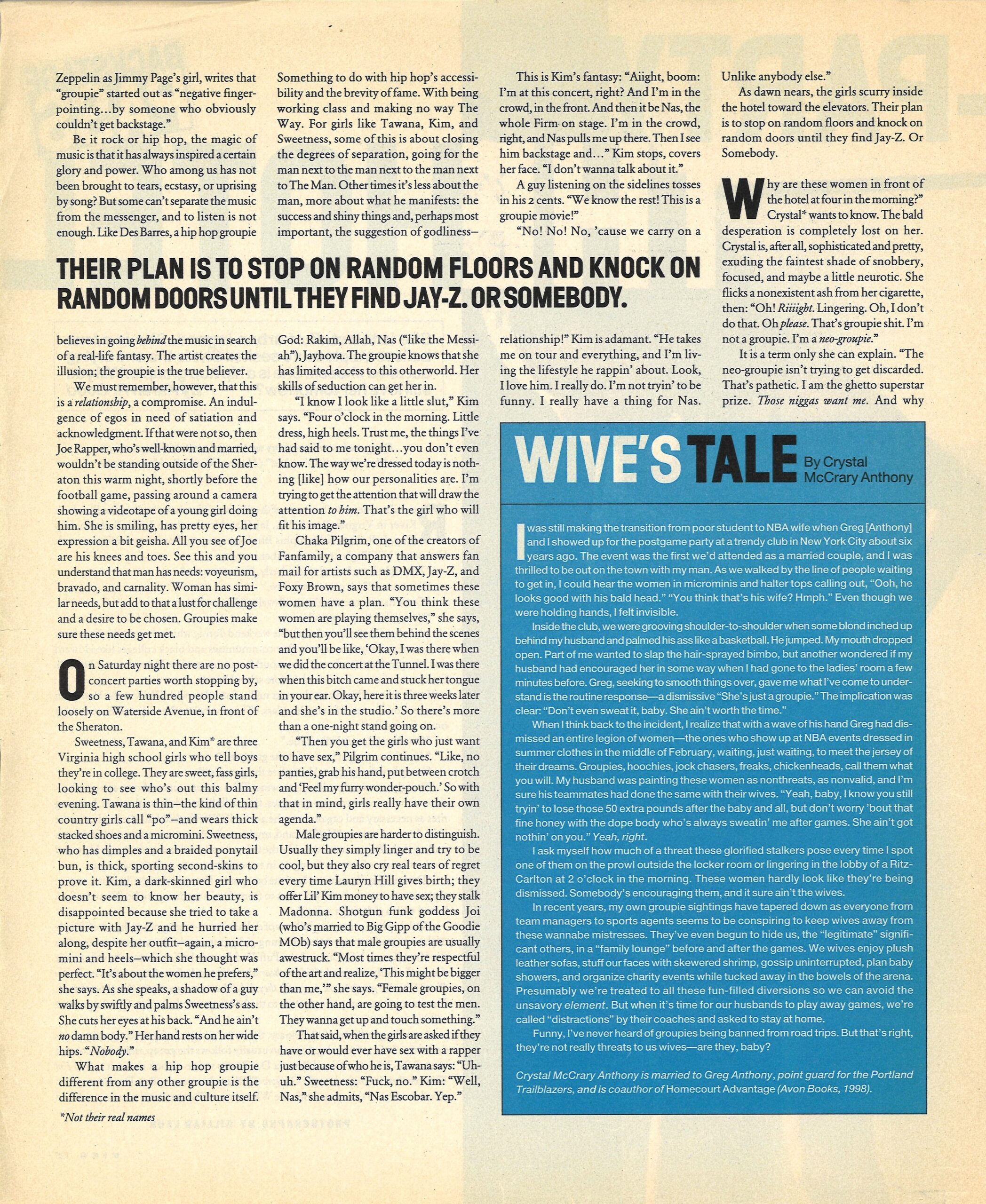

Why are these women in front of the hotel at four in the morning?” Crystal* wants to know. The bold desperation is completely lost on her. Crystal is, after all, sophisticated and pretty, exuding the faintest shade of snobbery, focused, and maybe a little neurotic. She flicks a nonexistent ash from her cigarette, then: “Oh! Riiiiight. Lingering. Oh, I don’t do that. Oh please. That’s that groupie shit. I’m not a groupie. I’m a neo-groupie.” It is a term only she can explain. “The neo-groupie isn’t trying to get discarded. That’s pathetic. I am the ghetto superstar prize. Those niggas want me. And why shouldn’t I enjoy being desired?”

Crystal, a tiny woman with soft hair cut low and skin the color of weak tea, pads around her friend Gongo’s Lower East Side, New York City apartment in fuzzy socks, loose blue jeans, and a cozy turtleneck that could swallow her small frame. Gongo and his three friends wander the flat. They pass reefer, flip TV channels, and occasionally interject.

Crystal is the ’90s progression of Des Barres in that the attraction to celebrity is still about the power and the glory, claim and sex. But for Crystal, fame isn’t the goal. It’s about money, which she believes grants freedom and certain liberties. No struggling like her parents with two mortgages, grease marks around the light switch, and ’70s green velvet everywhere. Maybe, she admits, it’s also something to “blackify” her, because she’s biracial with a Jewish last name. “A little ghetto dude on my arm with a six-pack and fly Hilfiger latest something or other. I feel like people can’t play me if I’m his fly bitch—‘cause they don’t. you know how nice they are to me?” She laughs. “I love it when people are nice to me that way.

Crystal, who is from a working-class neighborhood in Suffolk County, Long Island but now lives in Manhattan, does not work but likes nice things. She dates accordingly. “There are definitely fly niggas about,” Crystal says, “but power takes it to the next level.” She pauses, then, gives estimation:

“Have you ever been to Switzerland?” she asks.

No.

“It’s beautiful. It’s beautiful this time of year.”

So is Morocco, she recalls, and so is Holland, which she visited with a rapper, whom she’d rather not name, while he was touring Europe a few years ago. She says she’s no concubine. “I [participate in oral sex], it’s true. But I do other things with my day. I ski, read, go horseback riding. I shop.”

“You’re a dirty whore,” Gongo interrupts, and his friends giggle like school-girls. Crystal turns from her couch seat to face him, but not immediately. First she blinks.

So I’m a dirty whore?”

“You’re a dirty whore.” Not ho. Whore.

“You know, that’s interesting, because I actually like to be called a dirty whore when I’m in bed with men. It gets me hot,” she says and doesn’t blink. “So that would make sense. Oh well.” Crystal sits back and crosses her arms. “I’m just saying, keep it real. Sticks and stones may break my bones…label, label, label.”

Crystal recently completed film studies at New York University, where she wrote psychological shorts about dolls and two others: Niggas Don’t Love You and White Men Don’t Love You Either. “Everyone gets hurt in both films,” she says. “Everyone gets hurt all the time.”

In the relationship between artist and groupie, women offer their bodies and men use status and shiny toys as bait. Nothing personal. As Crystal says, “Love is about love. This is something else.” In this arrangement, the question becomes, what, if anything, is compromised? Crystal has some idea. “One time,” she says slowly, “I sorta got into this situation,” she continues, choosing her words carefully, “where I got really fucked up and I think a whole bunch of people fucked me. So, you know,” she says, lifting an eyebrow, “rape is pretty compromising.”

That was two years ago, in New York, in a club she’d rather not name. What she will say is that there were lots of hip hop artists present. “A lot of mean dick-sucking goes on,” she begins, kind of cryptically, “but not all of it is consensual. I try to think that rape is never my fault and move past it.” Later she will admit, casually, that “lots of people get raped; it was just a part of my destiny.”

Some of this is about the music, as violence and disrespect condoned in one form can only lead to violence and disrespect condoned in another. Some of this, however, is part of the deal. The adoration of celebrity is hero worship. And to worship a hero is to trade part of yourself for something that’s not real. A hip hop groupie sacrifices herself to the heightened emotionalism, eroticism, and rhythm of colored men who think themselves gods. In exchange, the groupie, when picked, gets to feel like the Chosen One.

That, to Crystal, is exactly the point.

“When he comes through I think I’m in a fucking rap video,” she says of her current rapper boyfriend. “I’ve got the fly lingerie. Crazy shit is jumping off.” She pauses. “Unless you’ve been around people who are so powerful, you don’t understand why it’s such an aphrodisiac. When you’re around a man and everybody around him is sweating him. [Getting with him.] All day long. That’s hot.” A flick of a cigarette, a crossing of arms. “And that’s that.”