Bubbling Brown Sugar

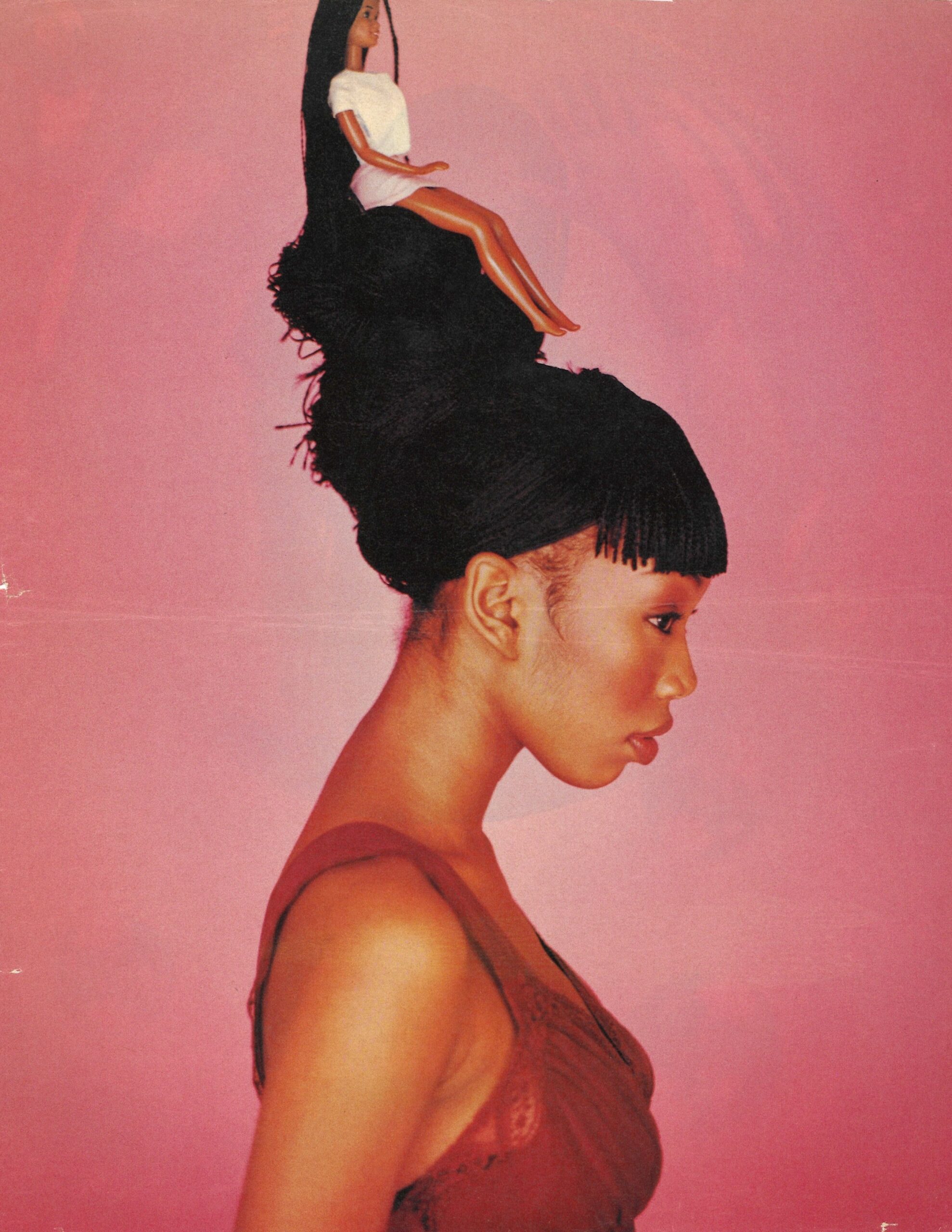

“Bubbling Brown Sugar: Brandy Norwood wants you to know that she’s not moving out of her mother’s house—and that she’s a grown-ass woman nonetheless. Karen R. Good gets intimate with the girl in the plastic bubble”

Vibe Magazine

Karen R. Good

April 1998

All Right Karen. What kind of question you gon’ ask me? At 19, Brandy Rayana Norwood has done five years as a Professional Celebrity; so she’s charming and astute. But, being 19, she’s still inquisitive and has not yet mastered subtlety; so she prods. Come on.

The writer has choices. I’ll tell you this much, I say. I’m just trying to find out who the real Brandy is.

And that’s the thing with curiosity and truth. A nerve’s struck. What? She says, as if, somehow, she saw this coming. The Brandy that’s out now ain’t real?

Nobody wants to read this story. Because the only things you really know about Brandy are the things she wants you to know: that she likes McDonald’s hamburgers, that Whitney Houston is her favorite artist, and…by this time, you don’t care.

Brandy seems to be a very good girl who does very good things. She is the All-American teenager sans the angst and the slack. She is very, very cute; earns very good grades from her very private tutor. She’s managed by her mom. Brandy does not drink, she will not smoke, and she goes to Avalon Church of Christ with her very together parents and cute younger brother. Every blessed Sunday (when she’s in town).

Brandy has suffered for this good reputation. She is the bubbly, popular girl whom some rebelliously can’t stand, probably because she reminds you of all the things that you are not. “I’m safe,” she tells me from her home in Los Angeles’ San Fernando Valley. “Sometimes too safe. I want every move I make to be right. Like, I thought it was a good idea for me to go to the prom with Kobe Bryant. He’s a guy with a good image; comes from a good family. Every move that I make in my career, I want to make sure it complements me. [When prom dates become career moves, you know stakes is high.] That’s why nothing really negative has come out of my life, because I try to make everything as right as I possibly can. Not to be perfect but…”

Exactly how can one playa-hate Brandy?!? Because when you think about it, there’s never really been another (black?) girl like her. Her first album, Brandy, released when she was just 14 years old, sold four million copies, driven by the platinum single “Baby” and the gold singles “I Wanna Be Down” and “Brokenhearted.” Her 1995 dong “Sittin’ up in My Room,” from the femme fatale-laden Waiting to Exhale soundtrack, sold more than a million copies. She stars in Moesha, the only television show that makes UPN worth a damn. She was the lead in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella, handpicked by Whitney Houston, the project’s fairy godmother/executive producer. Viewed by 60 million people, it was ABC’s highest rated program in 13 years.

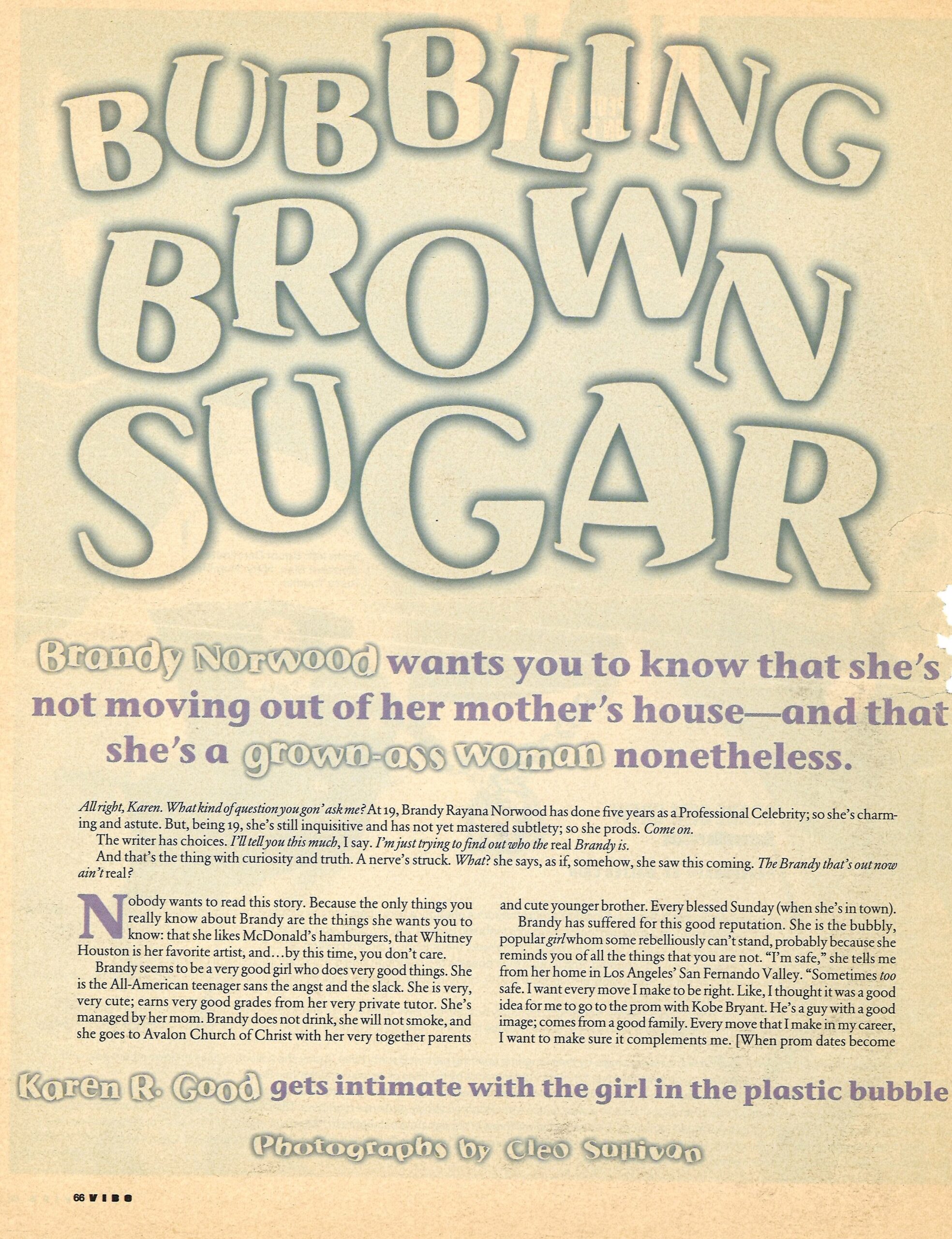

Brandy’s image personifies the virtue of innocence that William Blake wrote about centuries ago. Dimpled Mase plays with it. Janet tries terribly to shake it. Brand, however, embraces it. “I think my innocence is marketable,” she says, sitting up in her all-the-way-brown, dollhouse-perfect bedroom; a mocha-colored rug with her name knitted into it covers the floor. “And it works, the way I am. It works. I mean, that’s what people know me as. That’s why people call me a phony.” She’s 19, still in the process of figuring out who she really is, and everything she touches sells off the hook. “People think that [image is] too overdone,” she says with quiet insistence. “But that’s me.”

But you don’t buy it. It’s because of her eyes. They always seem far, far away and betray that wide, glorious smile. It’s a detachment inherent in Aquarians—always thinking three steps ahead—but also occurs when you grow up on stages and when your whole life is, essentially, scripted. I see Brandy in a plastic bubble with a shiny, sharp thing hidden behind her back.

So here’s a real personal question.

Oh God, you’re not going to ask me about sex are you? Oh God, don’t ask me about sex. Do they want to know that for real? [Tape clicks off]

Tonight on the set of Moesha, they’re taping the episode in which Moesha gets a tattoo on a dare from her friends. Her father discovers this and calls her a slut. The set—standard pop-up house, rife with black art—isn’t nearly as interesting as the studio audience. A comedian keeps the crowd hyped and laughing during the pauses between scenes. Black and Latino teenagers have mini-talent contests and rush to get autographs from cast members during the breaks. There’s a DJ who plays Usher’s recent “You Make Me Wanna…,” a song by another platinum pubescent. Everyone sings along.

Brandy and her friends Shay and Winter are watching old episodes of Moesha to pass the time in a trailer while wardrobe and makeup people do prep work. Winter, at first, is guardedly silent but politely smiling. She’s use to people scrutinizing her friend. “Brandy’s the sweetest person,” she says, “and she’s like that with everybody. She switches the roles on you. You hate her, and she’ll be the nicest person to you. You don’t fight fire with fire where she’s concerned. She wants people to know, ‘This is really me.’ She wants that so bad.”

Shay and Winter have known Brandy since 1994, when she lived in Carson, the middle-class suburb between Gardena and Compton, back when Brandy thought she could do folks’ hair, but her play clients would leave with scorched and buttered foreheads. Those days, she lived with her parents in the same house that the anointed gospel quartet the Clark Sisters used to rent. Brandy’s mother and father, Sonja and Willie Norwood, are here at Moesha; they’re the kind of conservatively hip, fortysomething parents who give each other pounds.

Brandy steps from stage left to center stage, along with the rest of the cast, and thanks everyone for coming. Her meet and greet is shorter than usual tonight because a stalker is said to be in the house. “She used to put 187 in my pager and threaten me,” Miss Norwood says of the obsessed fan who said her name, too, was Brandy. “She left a number in my pager that I would call back, and it would be Davis Funeral Home. That number used to come on my pager every week. I was scared to death.”

But that’s not the only scary stuff on the Moesha set. Countess Vaughn—who plays Kim Parker, one of Moesha’s best friends on the show—gives this writer a cold hello. Between the stalker and the shade, the otherwise jovial setting is unraveling.

Out on the streets, there are rumors that Brandy and Vaughn don’t get along. “I think she’s very funny, very talented,” Brandy says. “I just feel like she wants to be in the position I’m in. People tell her, ‘You’re the reason why the show’s successful.’ And she’s told me that before. And she’s called me a bitch—to my face. She said, ‘I’m the reason why the show is successful, bitch.’ In front of a lot of people. And I looked at her like, Wow. I couldn’t say nothing about her because I wasn’t about to.” That’s just who Brandy is—a little in control, a little confident, mostly adult. Kinda. “She knows,” says Brandy of Vaughn. “She wakes up and looks at herself in the mirror and she gets disgusted. I don’t.” Life isn’t a fairytale.

Brandy says that, with Cinderella, what she didn’t want to do was over-act. She wanted to be natural. After all, this wasn’t Cindy Eller, the 1991 ABC Afterschool Special remake of Cinderella where, instead of a glass slipper, the heroine got a worn sneaker. “It was really hard because it was like a proving thing. It was like, I was the first black Cinderella…Can she do it?And I just had to prove to everybody that I could. Because I never did Broadway. I’ve only been on Moesha. I’ve only been an R&B pop singer.” Those “onlys” are killing me. “I want to play something. I want to have a character that’s totally different than me. Because I don’t want people to say, ‘That was easy for her to do.’ ”

Then there are those revealing contradictions. Brandy was interested in playing Tisean (Tee Tee) in Set It Off—a single mother working for a janitorial company who starts robbing banks to make ends meet and is eventually killed. “I didn’t think I was ready for that,” she says. “I probably would have been fake playing a part like that because that’s not me. My mom wouldn’t let me do anything like that.”

Freddie “Paw Paw” Bates, Brandy’s grandfather on her mother’s side, is a self-determined businessman down in McComb, Mississippi who has owned service stations, a cab service, several apartments, and a liquor store. Been on this Earth almost 80 years now, and in all this time, the elder Bates has never worked for a white man. Ever. “That’s right,” his daughter Sonja says proudly. “Never.” (And yeah, Paw Paw used to sing Brandy to sleep.)

Freddie Bates was never blessed with sons; so Sonja, the youngest of his two daughters, followed in her father’s business-first footsteps. Her gestures suggest the splendid pageantry of a black woman raised in the South. Look at her, and you can tell that before she surrendered to God, while she was in college, she smoked Kools, joined Alpha Kappa Alpha, drank liquor strong, and cussed folk quick. After she found Him, she met Willie Norwood, a gospel musician and branded member of Omega Psi Phi fraternity. She jumped the broom; bore babies—a daughter, Brandy, and then a son Ray J. Trained them up in the way they would go.

Which brings us back to Paw Paw, self-determination, and white men. Atlantic Records Vice President and General Manager Ron Shapiro is, technically, Brandy’s boss and, most certainly, a white man. But he has had little to do with how she is seen, who she is, what she will be. Thatself is determined by Sonja Norwood. “These are very rational, smart people,” says Shapiro of the Norwoods. “Brandy knows more than she realizes. When we push her into coming up with answers and ideas about herself, she very sweetly thinks she needs help then defines herself perfectly appropriately. Her parents became very skilled managers over the course of the project.

“There’s never been an adversarial relationship between us and her parents,” Shapiro says. “There were some on the past record, which I think was normal, because they were learning the business.”

Brandy’s father, Willie Norwood Sr., sums up succinctly what he’s learned: “If you understand sharecropping, you understand the music industry.”

But there’s more to the business than dollars and cents. “They were concerned with how she looked, where she went, the things she did and said,” says Shapiro. “I have no quarrel with that.” That’s probably a good thing.

“No one,” Sonja states with mindful eyes, settling into her night chair in her room, in her Los Angeles house, which she is still working on but is very proud of, “no one is going to have the opportunity of taking the principles that we’ve instilled in my child and shape her into somebody else.” Period. That’s the unsaid that comes after everything Sonja says, an indubitable period.And her pronouncements are almost biblical in their finality. Like this one, from the Book of Sonja, on the shook: “I’ve been told that I intimidate people. But, to me, that’s a sign of weakness on the part of the person that’s supposed to be intimidated. If you allow me to intimidate you, then you shall be intimidated.”

Vulnerability hews through her voice once, when she speaks of younger brother Ray J., who is relatively scarce this weekend. I see him only on the day of the Moesha taping, and he’s on his way out. “I just stopped by to give Bran support. It’s not my show, you know.” He offers a Charms Blow Pop and disappears. “One of the biggest downfalls for me was the fact that Ray J.’s music was not accepted in the market,” Sonja says, as if one could just expect a successful pop music career like one expects regular dental checkups. “It was a great big expectation, but it didn’t work. I’ll tell ya, for five months, every day of the week, I cried every single day. I didn’t cry in front of him.” But she is crying in front of me. Right now. Damn.

Though Brandy isn’t moving into her own place anytime soon (she’s actually building a suite onto the family house), Sonja’s 16-year-old son will move out once he turns 18. “That hurts more than anything, that he’s gonna be gone, you know? He’s my confidant. When I cry, I go to him because he listens to me.” “Stage mother” is a name that’s been associated with Sonja Norwood. And though she does demand that her children work hard, she ain’t Joe Jackson, father of Jane and Michael, grandfather of Bubbles.

And time has proven Sonja right on one thing. “I can sell my kids,” she says at the photo shoot for Brandy’s second album, gesturing toward the Pacific. “I can sell my kids to the ocean, and the ocean would buy them.”

Men jock Kobe Bryant; women love him. He’s six foot seven, 210 pounds, and gets called names like Prodigy and Golden Child. At 19, he is in his second season with the Los Angeles Lakers and speaks Italian fluently. Pretty nice catch, huh?

Kobe Bryant took Brandy to his Lower Merion High School senior prom in Philadelphia. That weekend, they spent three days together in Atlantic City (sleeping in separate rooms). On the first night, Kobe took her to see Barry White. “I was like, Barry White?” Brandy recalls, laughing. “Kobe, what you know about Barry White? Boy, please! Practice what you preach.” Cain’t nobody say that the brother didn’t try.

“What didn’t happen with Kobe and me is, he was just becoming a basketball player and I had my career,” she explains. “I liked Kobe; he had that confidence and innocence about him that attracted me. It was like he’d never been through nothin’. And I had a crush on Wanya.” As in Wanya Morris, the 24-year-old big, big ol’ pop star from Boyz II men. He’s the Boy holding Brandy around the waist, from the back, in her graduation day photograph (from City of Angels High School) in her bedroom. The Boy Brandy’s had a crush on since before she opened for Boyz II Men’s 1995 North American Tour. Even before her first single, “I Wanna Be Down,” knocked his quartet’s “I’ll Make Love to You” from Billboard’s No. 1 pop slot. That feat prompted Morris to call young Brandy to offer his congratulations.

“He was my favorite because his vocal runs are out of the ordinary,” she says, ever the professional. She also calls him the “special person in my life,” words tinged with the gentle inflections of a lullaby. “But he didn’t like me. I was fifteen years old—what did he want to do with me?” Go to jail? I offer, and Brandy laughs.

For her sweet 16th birthday, Boyz II Men, during the 1995 NBA All-Star Weekend, serenaded Brandy and presented her with a diamond tennis bracelet, gold, heart-shaped earrings with diamonds, and a matching pendant.

“I think I fell in love with him over the years,” Brandy says, sitting on the floor of her room, legs crossed, head tilted dreamily to one side.

In love? Brandy. Girl, what you know about love?

“I don’t,” she says; then: “I didn’t. But I am in love. Or as my mamma always says, I’m in love for what I know love to be.”

Sonja, who once promised Wanya that “Boyz II Men would become a trio” if he stepped to Brandy before she was 18, now, in Brandy’s room, stares at the television wistfully as her daughter prepares for her date with the singer. While Kobe and the Lakers play the Clippers on the screen, Brandy is slipping a short black jacket over a long, tight, informal glittery dress. “Every line and curve you have, I can see it,” Sonja says, shaking her head in the adoring, helpless, vigilant way mothers do when they know their babies are grown. Brandy ain’t paying her mama no mind. Wanya arrives then, looking peevish, comes upstairs to greet Sonja. He and Brandy quickly leave, feeling for each other’s hands. Sonja watches, sighs, looks back at the TV, sighs. “My prayers are still goin’ up to the Good Lord for Kobe.”

Meanwhile, Brandy’s out with the boy from Illadelphia’s Richard Allen Projects. I tell her that, deep down, I always thought Fredro from Onyx (and now a regular on Moesha) was more her type. Wanya just seems so, um, well, Boyz II Men. That said, Brandy comes out of her face, letting me see her indigenous black girl. “Nooow, I wouldn’t say that Mr. Morris was a roughneck; but, ahh, he ain’t—”

Boyz II Men all the time? I venture.

A tight laugh. Knowing. “Sometimes he can go a little Jodeci on you, knowwhatI’msayin’?”

A conversation one January afternoon on New York’s Hot 97 radio station between Bad Boy recording artist Mase and on-air personality Angie Martinez:

Angie: Mase, so what kind of girls do you like?

Mase: I like ghetto girls, like Mariah Carey and Brandy.

Angie: Brandy’s a ghetto girl?

Mase: Nah, I ain’t…I ain’t getting into that, Angie.

When Brandy talks about Mase, her words begin to cometogetherfastlikethis. She gets all excited and exaggerated and Sheneneh-boo. “I’m a big fan of Mase. A huge fan. I want to do a song with Mase so bad! It’s like Mase is kinda like me, laid-back.”

Okay, that’s not so far off. I see the connection. “I saw him on Vibe, and he was telling the audience, ‘Y’all, [Sinbad’s] not going to be able to hear me if you all keep screaming.’ It’s like, awww, the little boy next-door. It was so innocent.” There’s that word again. “Mase is approachable, like you could reach out and pinch his little cheek.” Brandy tells me that she is also feeling Rakim and Keith Murray. And again I have to tease her. Brandy, you know you like them roughneck boys.

Brandy gives me a look that could be a wink. “I might be a little sheltered,” she says. “But I know the hip hop for real. You know, I was so jealous of Mariah when she had all of ’em in her video. I wanted to be next to Puffy.”

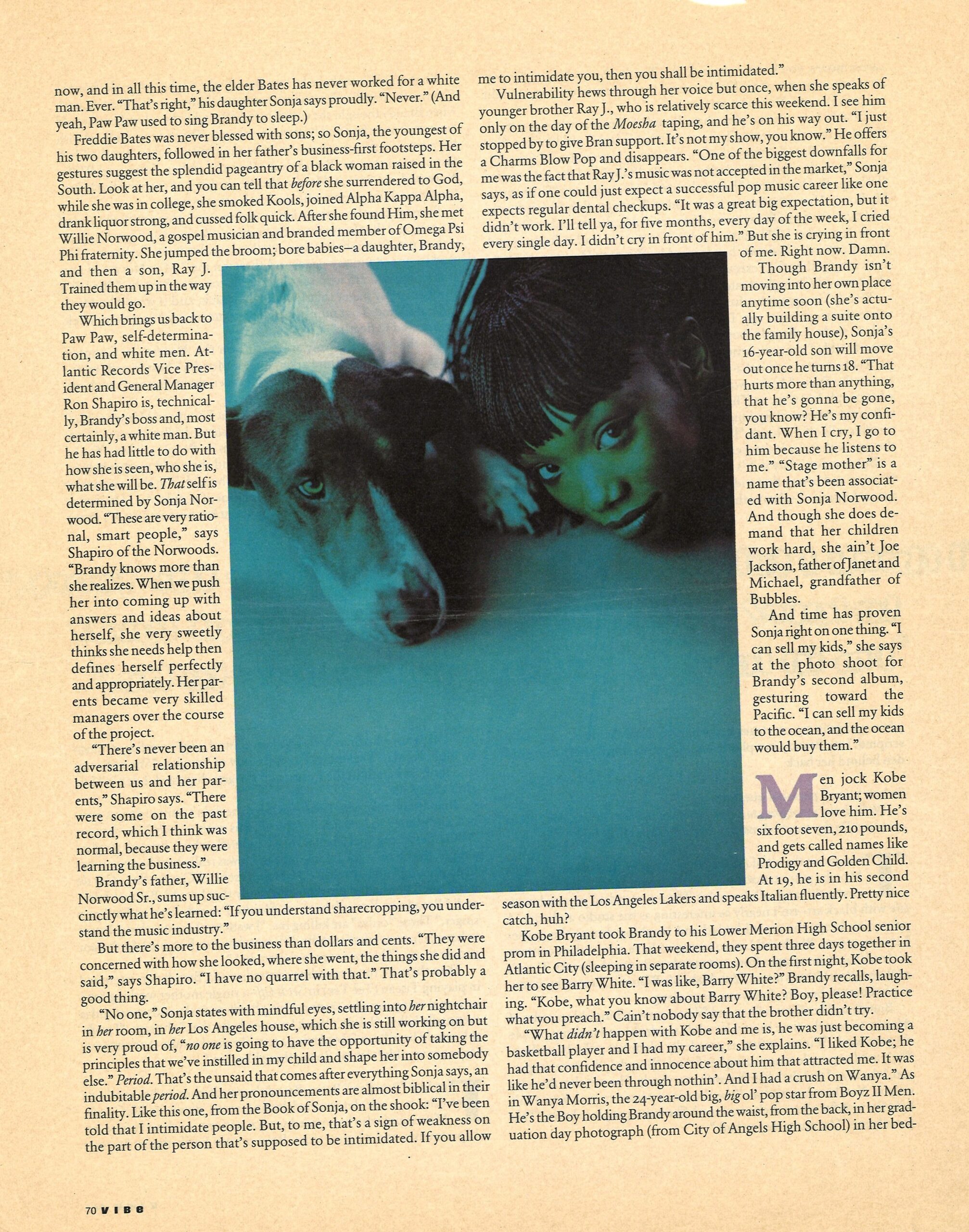

The location for Brandy’s album-cover photo shoot (the tentative title is Never Say Never) is a mansion in the hills of Malibu—a home guarded by the kind of concrete lions that inspired Sonja Sanchez. Brandy sits in a chair that, from where I’m standing, seems to be resting on the Pacific Ocean. But this place is anything but pacific. Stylists, assistants, and other photo-shoot types swarm around her. They’re fussing with her makeup. They’re fussing with her hair, her clothes. They’re tilting her chin to just…that…angle. You almost feel sorry for her. Almost.

Brandy is learning to be her own protector. When a photographer says jump, Brandy no longer smiles and say, “How high?” Instead, she has this look that’s less of a stare than an extended glance. It bores right through you and says, “Please, don’t fuck with me.” In the nicest way. Her braids—soon to be shed because she wants a change, a slightly older look—are a river of black ribbons; her feet are mango-oiled.

Her new songs, the Rodney Jerkins-produced “Happy” and “Never Say Never,” are playing behind her. The softness of her voice speaks more to style than to youth. A long-coming sensuousness has replaced the whimsy and then you realize: Damn, Brandy’s grown. “You know, this is not like ‘Sittin’ up in My Room,’ because I was sixteen then, and I did sit up in my room talkin’ about, Oh, God, what’s Wanya doin’? Now I’m nineteen. And it’s like, You know what? You’re going to respect me.

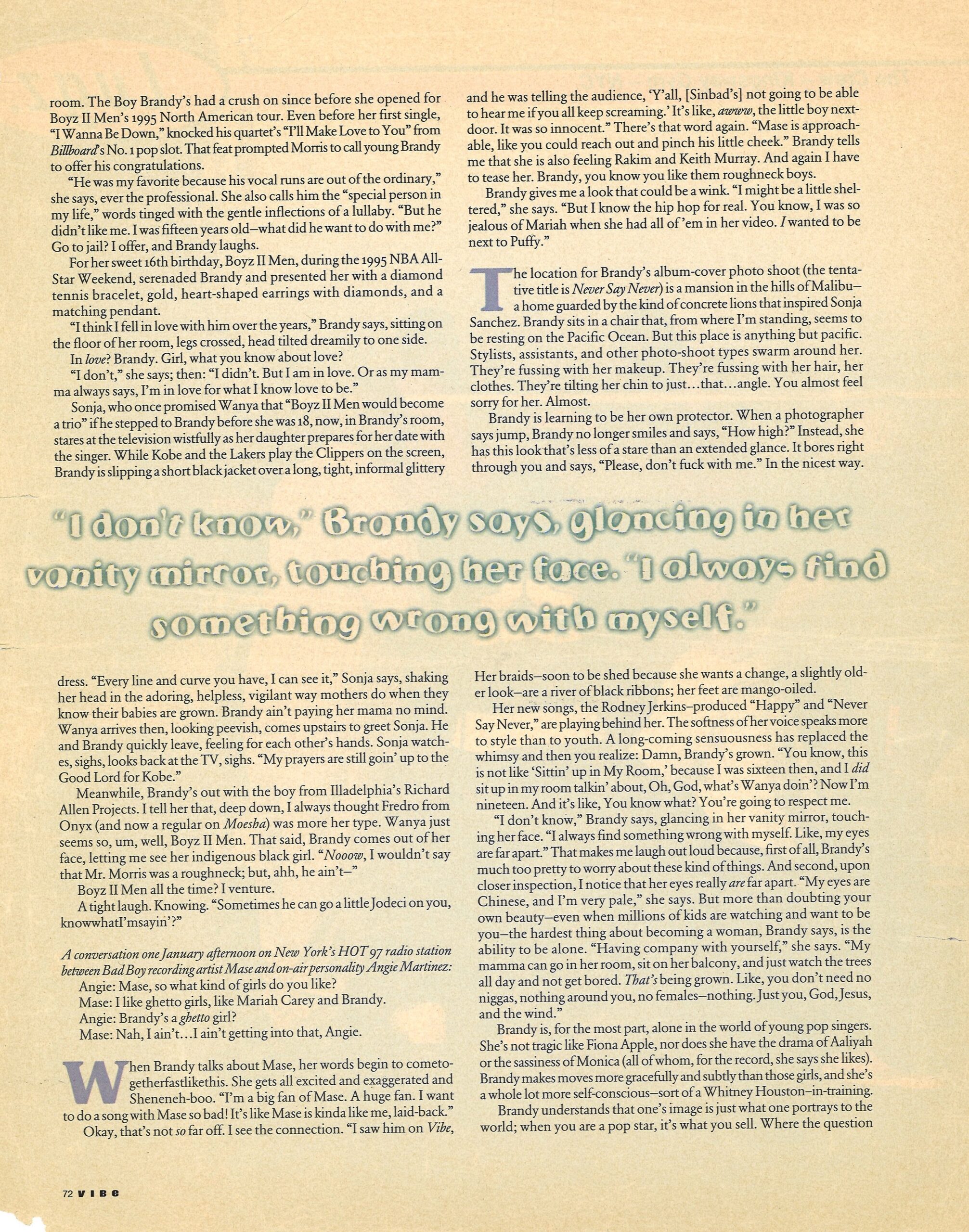

“I don’t know,” Brandy says, glancing in her vanity mirror, touching her face. “I always find something wrong with myself. Like, my eyes are far apart.” That makes me laugh out loud because, first of all, Brandy’s much too pretty to worry about these kind of things. And second, upon closer inspection, I notice that her eyes really are far apart. “My eyes are Chinese, and I’m very pale,” she says. But more than doubting your own beauty—even when millions of kids are watching and want to be you—the hardest thing about becoming a woman, Brandy says, is the ability to be alone. “Having company with yourself,” she says. “My mamma can go in her room, sit on her balcony, and just watch the trees all day and not get bored. That’s being grown. Like, you don’t need no niggas, nothing around you, no females—nothing. Just you, God, Jesus, and the wind.”

Brandy is, for the most part, alone in the world of young pop singers. She’s not tragic like Fiona Apple, nor does she have the drama of Aaliyah or the sassiness of Monica (all of whom, for the record, she says she likes). Brandy makes moves more gracefully and subtly than those girls, and she’s a whole lot more self-conscious—sort of a Whitney Houston-in-training.

Brandy understands that one’s image is just what one portrays to the world; when you are a pop star, it’s what you sell. Where the question comes in is when you can’t tell what belongs to the world and what belongs to you. But she understands where she comes from, what her truth is.

She’s a lot like me, with loving parents who meant the best for her; kept her protected, maybe too much so. Rules sometimes give you an awareness of age—kind of a limit to what you can and cannot do, and when. Brandy has a certain understanding about the world after growing up under such fierce gazes. And she acts accordingly.

Brandy’s father knows what his children are going through. Willie Norwood is his daughter’s voice coach and a Sunday School teacher. He’s not unaware of his daughter’s struggles. “How are two imperfect people going to have perfect kids?” he asks. “They’re gonna try different stuff, you just have to pray that they find their way.”

For now, Brandy is staying home. She says she’s sometimes scare to sleep alone and would prefer to have family and friends around her. “My mother does not want to let me go,” Brandy admits. If Brandy did move, she says she would live in New York City. She romanticizes about dressing up in fly suits, with long scarves flailing behind her. It’s the one place in the world that understands insomnia, so at least she’d have some company in the crepuscular streets. If Brandy did move, she would live in New York City, because at least there, the seasons change. And bubbles, gloriously, burst.