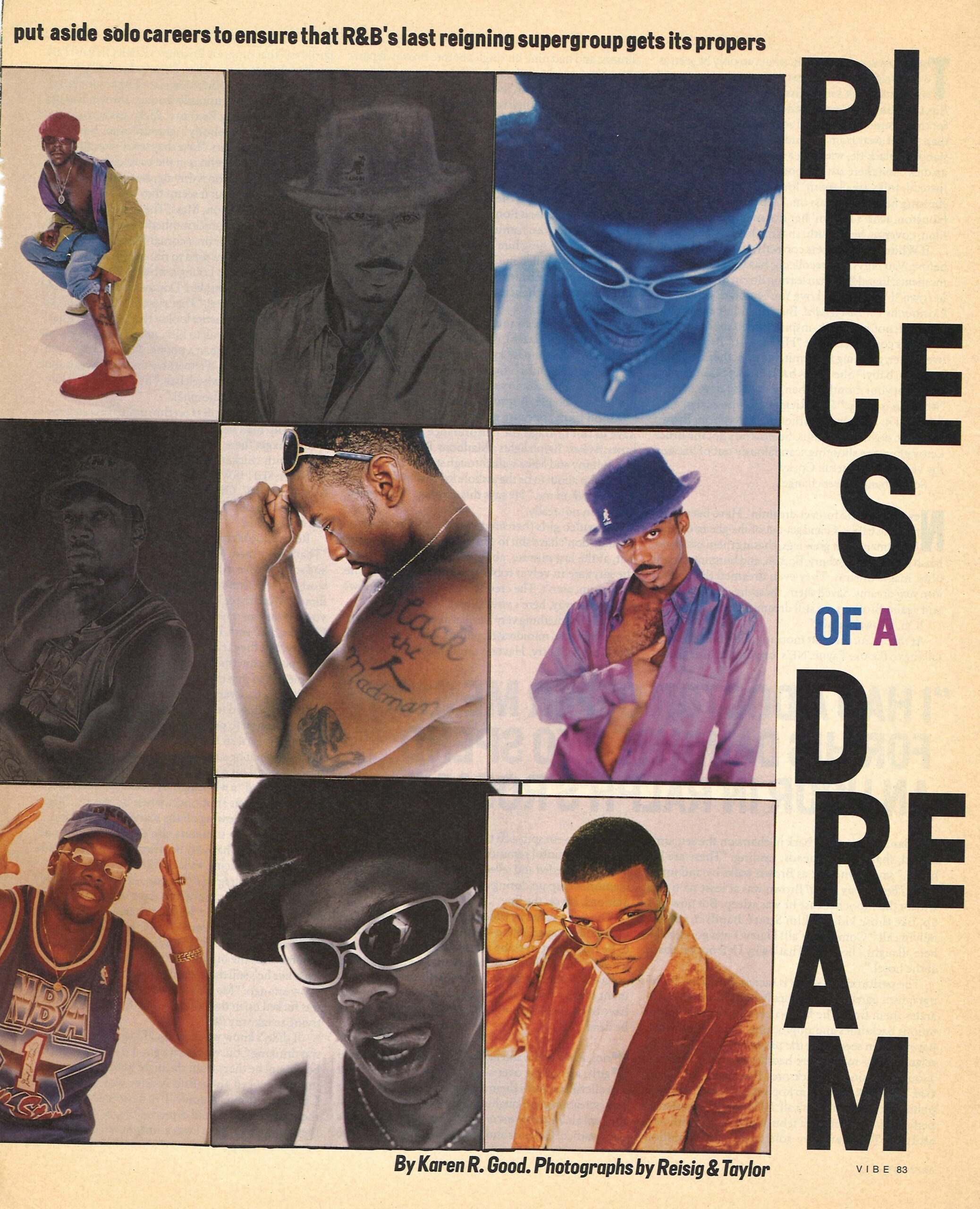

PIECES OF A DREAM

VIBE

Karen Good

November 1996

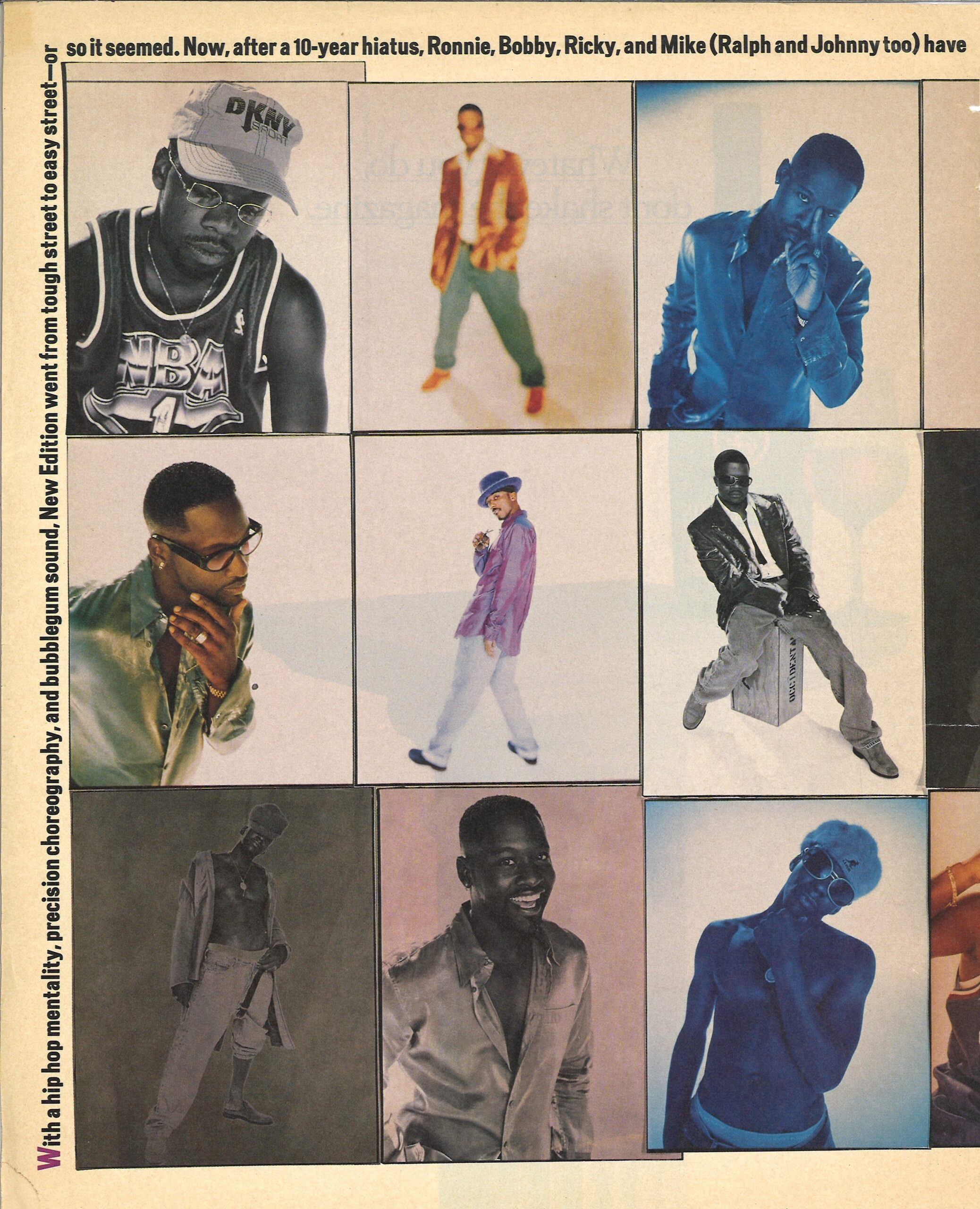

With a hip hop mentality, precision choreography, and bubblegum sound, New Edition went from tough street to easy street—or so it seemed. Now, after a 10-year hiatus, Ronnie, Bobby, Ricky, and Mike (Ralph and Johnny too) have put aside solo careers to ensure that R&B’s last reigning supergroup gets its propers.

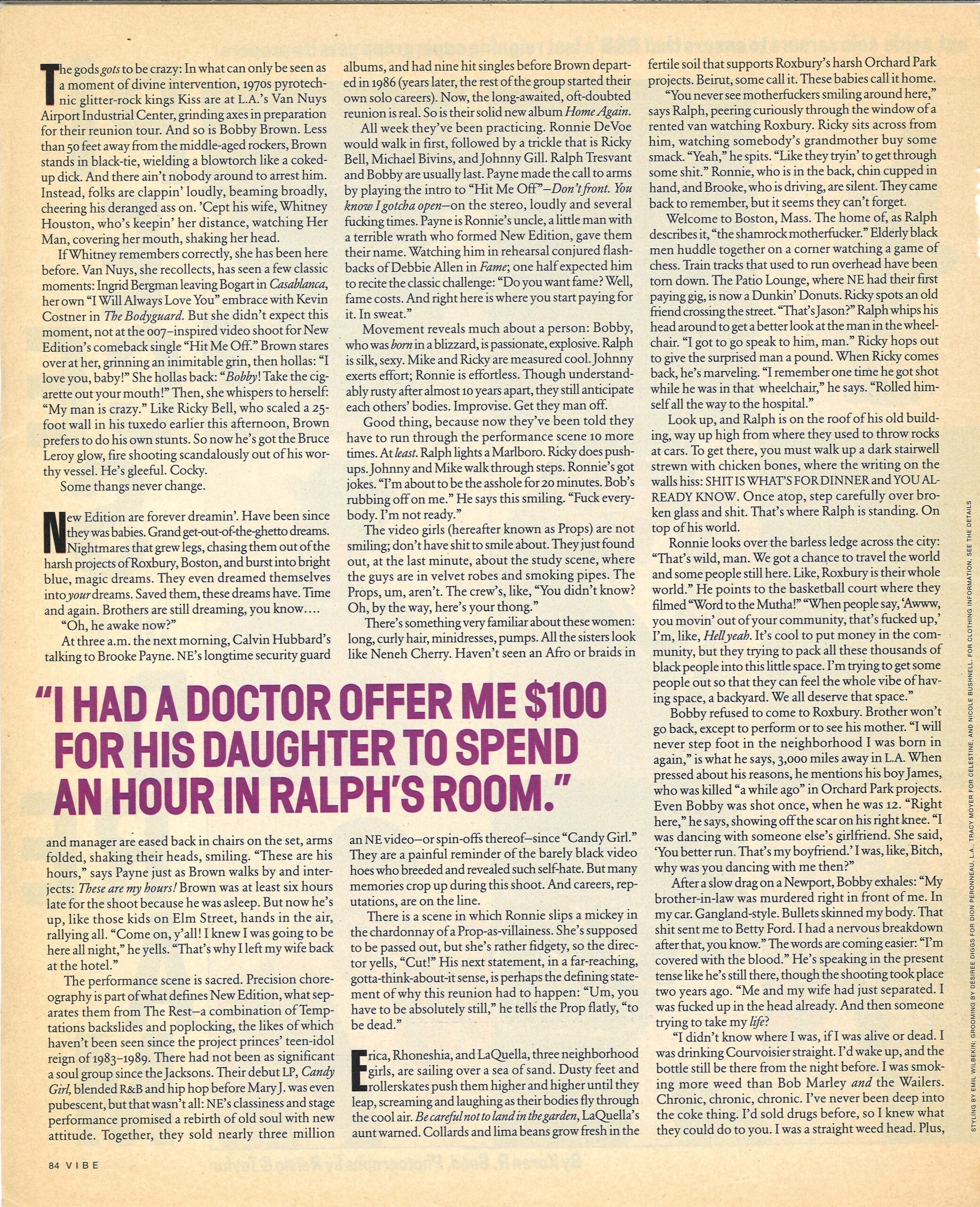

The gods gots to be crazy: In what can only be seen as a moment of divine intervention, 1970s pyrotechnic glitter-rock kings Kiss are at L.A. Van Nuys Airport Industrial Center, grinding axes in preparation for their reunion tour. And so is Bobby Brown. Less than 50 feet away from the middle-aged rockers, Brown stands in black-tie, wielding a blowtorch like a coked-up dick. And there ain’t nobody around to arrest him. Instead, folks are clappin’ loudly, beaming broadly, cheering his deranged ass on. ‘Cept his wife, Whitney Houston, who’s keepin’ her distance, watching her Man, covering her mouth, shaking her head.

If Whitney remembers correctly, she has been here before. Van Nuys, she recollects, has seen a few classic moments: Ingrid Bergman leaving Bogart in Casablanca, her own “I Will Always Love You” embrace with Kevin Costner in The Bodyguard. But she didn’t expect this moment, not at the 007-inspired video shoot for New Edition’s comeback single “Hit Me Off.” Brown stares over at her, grinning an inimitable grin, then hollas: “I love you, baby!” she hollas back: “Bobby! Take the cigarette out your mouth!” Then she whispers to herself: “My man is crazy.” Like Ricky Bell, who scaled a 25-foot wall in his tuxedo earlier this afternoon, Brown prefers to do his own stunts. So now he’s got the Bruce Leroy glow, fire shooting scandalously out of his worthy vessel. He’s gleeful. Cocky.

Some things never change.

New Edition are forever dreamin’. Have been since they was babies. Grand get-out-of-the-ghetto dreams. Nightmares that grew legs, chasing them out of the harsh projects of Roxbury, Boston and burst into bright blue, magic dreams. They even dreamed themselves into your dreams. Saved them, these dreams have. Time and again. Brothers are still dreaming, you know…

“Oh, he awake, now?”

At three a.m., the new morning, Calvin Hubbard’s talking to Brooke Payne. NE’s longtime security guard and manager are eased back in chairs on the set, arms folded, shaking their heads, smiling. “These are his hours,” says Payne just as Brown walks by and interjects: These are my hours! Brown is at least six hours late for the shoot because he was asleep. But now he’s up, like those kids on Elm Street, hands in the air, rallying all. “Come on, y’all! I knew I was going to be here all night,” he yells. “That’s why I left my wife back at the hotel.”

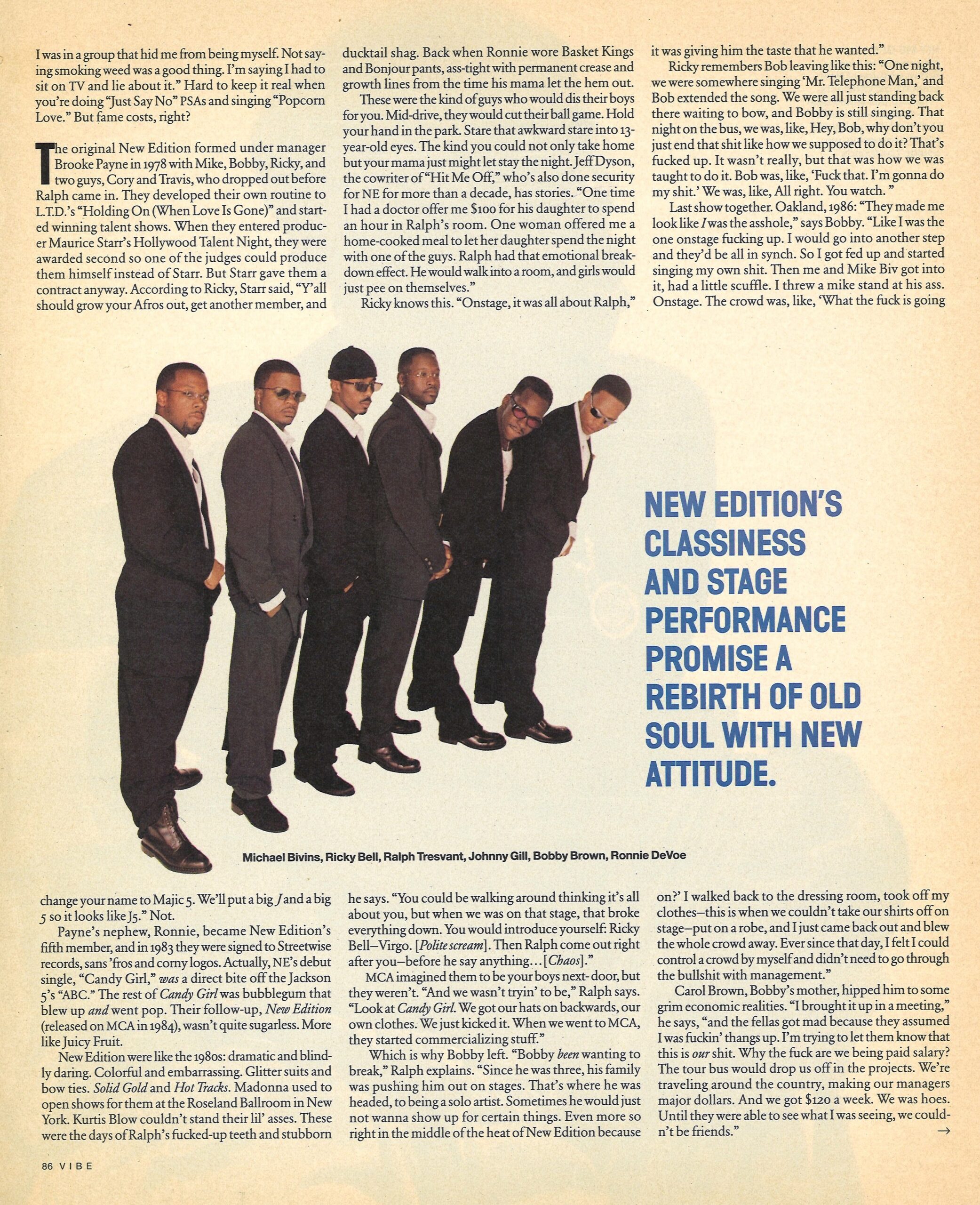

The performance scene is sacred. Precision choreography is part of what defines New Edition, what separates them from the Rest—a combination of Temptations backslides and poplocking, the likes of which haven’t been seen since the project princes’ teen-idol reign of 1983-1989. There had not been as significant a soul group since the Jacksons. Their debut LP, Candy Girl, blended R&B and hip hop before Mary J. was even pubescent, but that wasn’t all: NE’s classiness and stage performance promised a rebirth of old soul with new attitude. Together, they sold nearly three million albums, and had nine hit singles before Brown departed in 1986 (years later, the rest of the group started their own solo careers). Now, the long-awaited, oft-doubted reunion is real. So is their solid new album Home Again.

All week they’ve been practicing. Ronnie DeVoe would walk in first, followed by a trickle that is Ricky Bell, Michael Bivins, ad Johnny Gill. Ralph Tresvant and Bobby are usually last. Payne made the call to arms by playing the intro to “Hit Me Off”—Don’t front. You know I gotcha open—on the stereo, loudly and several fucking times. Payne is Ronnie’s uncle, a little man with a terrible wrath who formed New Edition, gave them backs of Debbie Allen in Fame; one half expected him to recite the classic challenge: “Do you want fame? Well fame costs. And right here is where you start paying for it. In sweat.”

Movement reveals much about a person: Bobby who was born in a blizzard, is passionate, explosive. Ralph is silk, sexy. Mike and Ricky are measured cool. Johnny exerts effort; Ronnie is effortless. Though understandably rusty after almost 10 years apart, they still anticipate each others’ bodies. Improvises. Get they man off.

Good thing, because now they’ve been told they have to run through the performancescene 10 more times. At least. Ralph light a Marlboro. Ricky does pushups. Johnny and Mike walk through steps. Ronnie’s got jokes. “I’m about to be the asshole for 20 minutes. Bob’s rubbing off on me.” He says this smiling. “Fuck everybody. I’m not ready.”

The video girls (hereafter known as Props) are not smiling; don’t have shit to smile about. They just found out, at the last minute, about the study scene, where the guys are in velvet robe and smoking pipes. The Props, um, aren’t. The crew’s like, “You didn’t know? Oh, by the way, here’s your thong.”

There’s something very familiar about these women: long, curly hair, minidresses, pumps. All the sisters look like Neneh Cherry. Haven’t seen an Afro or braids in an NE video—or spin-offs thereof—since “Candy Girl.” They are a painful reminder of the barely black video hoes who bred and revealed such self-hate. But many memories crop up during this shoot. And careers, reputations, are on the line.

There is a scene in which Ronnie slips a mickey in the chardonnay of a Prop-as-villainess. She’s supposed to be passed out, but she’s rather fidgety, so the director yells, “Cut!” His next statement, in a far-reaching, gotta-think-about-it sense, is perhaps the defining statement of why this reunion had to happen: “Um, you have to be absolutely still,” he tells the Prop flatly, “to be dead.”

Erica, Rhoneshia, and LaQuella, three neighborhood girls, are sailing over a sea of sand. Dusty feet and roller skates push then higher and higher until they leap, screaming and laughing as their bodies fly through the cool air. “Be careful not to land in the garden”, LaQuella’s aunt warned. Collards and lima beans grow fresh in the fertile soil that supports Roxbury’s harsh Orchard Park projects. Beirut, some call it. These babies call it home.

“You never see motherfuckers smiling around here,” says Ralph, peering curiously through the window of a rented van watching Roxbury. Ricky sits across from him, watching somebody’s grandmother buy some smack. “Yeah,” he spits. “Like they tryin’ to get through some shit.” Ronnie, who is in the back, chin cupped in hand, and Brooke, who is driving, are silent. They came back to remember, but it seems they can’t forget.

Welcome to Boston, Mass. The home of, as Ralph describes it, “the shamrock motherfucker.” Elderly black men huddle together on a corner watching a game of chess. Train tracks that used to run overhead have been torn down. The Patio Lounge, where NE had their first paying gig, is now a Dunkin’ Donuts. Ricky spots an old friend crossing the street. “That’s Jason?” Ralph whips his head around to get a better look at the man in the wheelchair. “I got to go speak to him, man.” Ricky hops out to give the surprised man a pound. When Ricky comes back, he’s marveling. “I remember one time he got shot while he was in that wheelchair,” he says. “Rolled himself all the way to the hospital.”

Look up, and Ralph is on the roof of his old building, way up high from where they used to throw rocks at cars. To get there, you must walk up a dark stairwell strewn with chicken bones, where the writing on the walls hiss: SHIT IS WHAT’S FOR DINNER and YOU ALREADY KNOW. Once atop, step carefully over broken glass and shit. That’s where Ralph is standing. On top of his world.

Ronnie looks over the barless ledge across the city: “That’s wild, man. We got a chance to travel the world and some people still here. Like, Roxbury is their whole world.” He points to the basketball court where they filmed “Word to the Mutha!” “When people say, ‘Awww, you movin’ out of your community, that’s fucked up,’ I’m, like, Hell yeah. It’s cool to put money in the community, but they trying to pack all these thousands of black people into this little space. I’m trying to get some people out so that they can feel the whole vibe of having space, a backyard. We all deserve that space.”

Bobby refused to come to Roxbury. Brother won’t go back, except to perform or to see his mother. “I will never step foot in the neighborhood I was born in again,” is what he says, 3, 000 miles away in L.A. When pressed about his reasons, he mentions his boy James, who was killed “a while ago” in Orchard Park projects. Even Bobby was shot once, when he was 12. “Right here,” he says, showing off the scar on his right knee. “I was dancing with someone else’s girlfriend. She said, ‘You better run. That’s my boyfriend.’ I was, like, Bitch, why was you dancing with me then?”

After a slow drag on a Newport, Bobby exhales: “My brother-in-law was murdered right in front of me. In my car. Gangland-style. Bullets skinned my body. That shit sent me to Betty Ford. I had a nervous breakdown after that, you know.” The words are coming easier: “I’m covered with the blood.” He’ speaking in the present tense like he’s still there, though the shooting took place two years ago. “Me and my wife had just separated. I was fucked up in the head already. And then someone trying to take my life?”

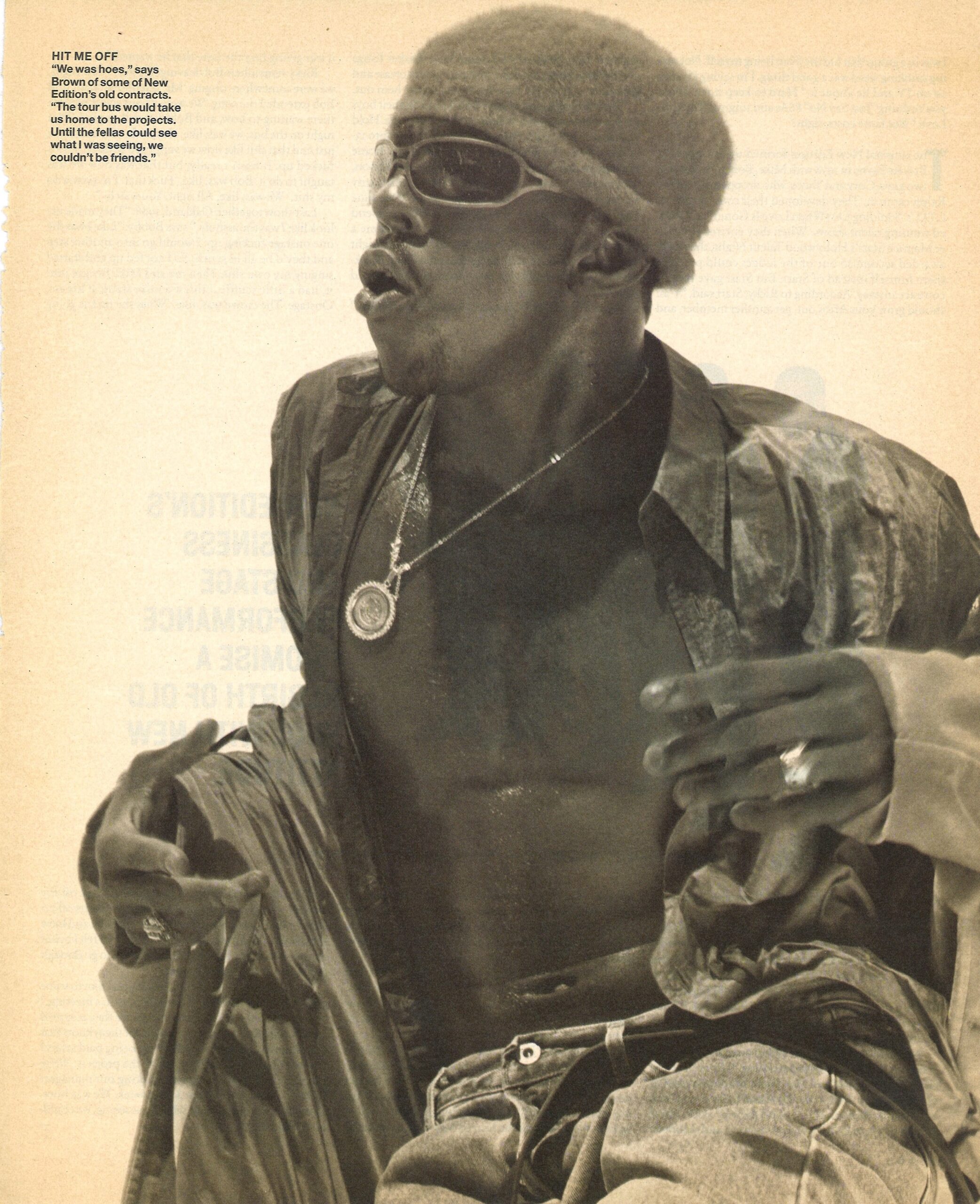

“I didn’t know where I was, if I was alive or dead. I was drinking Courvoisier straight. I’d wake up, and the bottle still be there from the night before. I was smoking more weed than Bob Marley and the Wailers. Chronic, chronic, chronic. I’ve never been deep into the coke thing. I’d sold drugs before, so I knew what that could do to you. I was a straight weed head. Plus, I was in a group that hid me from being myself. Not saying smoking weed was a good thing. I’m saying I had to sit on TV and lie about it.” Hard to keep it real when you’re doing “Just Say No” PSAs and singing “Popcorn Love.” But fame costs, right?

The original New Edition formed under manager Brooke Payne in 1978 with Mike, Bobby, Ricky, and two guys, Cory and Travis, who dropped out before Ralph came in. They developed their own routine to L.T.D.’s “Holding On (when Love Is Gone)” and started winning talent shows. When they entered producer Maurice Starr’s Hollywood Talent Night, they were awarded second so one of the judges could produce them himself instead of Starr. But Starr gave them a contract anyway. According to Ricky, Starr said, “Y’all should grow your Afros out, get another member, and change your name to Majic 5. We’ll put a big J and a big 5 so it looks like J5.” Not.

Payne’s nephew, Ronnie, became New Edition’s fifth member, and in 1983 they were signed to Streetwise records, sans ‘fros and corny logos. Actually, NE’s debut single, “Candy Girl,” was a direct bite off the Jackson 5’s, “ABC.” The rest of “Candy Girl” was bubble gum that blew up and went pop. Their follow-up, New Edition (released on MCA in 1984), wasn’t quite sugarless. More like Juicy Fruit.

New Edition were like the 1980s: dramatic and blindly daring. Colorful and embarrassing. Glitter suits and bow ties. Solid Gold and Hot Tracks. Madonna used to open shows for them at the Roseland Ballroom in New York. Kurtis Blow couldn’t stand their lil’ asses. These were the days of Ralph’s fucked-up teeth and stubborn ducktail shag. Back when Ronnie wore Basket Kings and Bonjour pants, ass-tight with permanent crease and growth lines from the time his mama let the hem out.

These were the kind of guys who would dis their boys for you. Mid-drive, they would cut their ball game. Hold your hand in the park. Stare that awkward stare into 13-year-old eyes. The kind you could not only take home but your mama just might let stay the night. Jeff Dyson, the cowriter of “Hit Me Off,” who’s also done security for NE for more than a decade, has stories. “One time I had a doctor offer me $100 for his daughter to spend an hour in Ralph’s room. One woman offered me a home-cooked meal to let her daughter spend the night with one of the guys. Ralph had that emotional breakdown effect. He would walk into a room, and girls would just pee on themselves.”

Ricky knows this. “Onstage, it was all about Ralph,” he says. “You could be walking around thinking it’s all about you, but when we was on the stage, that broke everything down. You would introduce yourself: Ricky Bell—Virgo. [Polite scream]. Then Ralph comes out right after you—before he say anything… [Chaos].”

MCA imagined them to be your boys next-door, but they weren’t. “And we wasn’t tryin’ to be,” Ralph says. “Look at Candy Girl. We got our hats on backwards, our own clothes. We just kicked it. When we went to MCA, they started commercializing stuff.”

Which is why Bobby left. “Bobby been wanting to break,” Ralph explains. “Since he was three, his family was pushing him out on stages. That’s where he was headed, to be a solo artist. Sometimes he would just not wanna show up for certain things. Even more so right in the middle of the heat of New Edition because it was giving him the taste that he wanted.”

Ricky remembers Bob leaving like this: “One night, we were somewhere singing ‘Mr. Telephone Man,’ and Bob extended the song. We were all just standing back there waiting to bow, and Bobby is still singing. That night on the bus, we was, like, Hey Bob, why don’t you just end that shit like how we supposed to do it. That’s fucked up. It wasn’t really, but that was how we was taught to do it. Bob was, like, ‘Fuck that. I’m gonna do my shit.’ We was, like, All right. You watch.”

Last show together. Oakland, 1986: “They made me look like I was the asshole,” says Bobby. “Like I was the one onstage fucking up. I would go into another step and they’d all be in sync. So, I got fed up and started singing my own shit. Then me and Mike Bivgot into it, had a little scuffle. I threw a mike stand at his ass. Onstage. The crowd was like, ‘What the fuck is going on?’ I walked back to the dressing room, took off my clothes—this is when we couldn’t’ take our shirts off on stage—put on a robe, and I just came back out and blew the whole crowd away. Ever since that day, I felt I could control a crowd by myself and didn’t need to go through the bullshit with management.”

Carol Brown, Bobby’s mother, hipped him to some grim economic realities. “I brought it up in a meeting,” he says, “and the fellas got mad because they assumed I was fuckin’ thangs up. I’m trying to let them know that this is our shit. Why the fuck are we being paid salary? The tour bus would drop us off in the projects. We’re traveling around the country, making our managers major dollars. And we got $120 a week. We was hoes. Until they were able to see what I was seeing, we couldn’t be friends.”

After Bobby went on to record (and become) King of Stage, Mike was thinking of Plan B. He saw Johnny Gill at a Whispers concert and asked him to join the group. Gil had scored a solo hit in 1983 with “Super Love,” and teamed up with Stacy Lattisaw on the hit single, “Perfect Combination.” Folks were already calling him Baby Luther, the next Teddy Pendergrass.

According to Johnny, Michael looked at him and said, “I really think you’re one of the baddest singers out. Do you feel like you’ve gotten your due as a singer?” “No, not really,” he replied. They went to MCA’s Jheryl Busby the next day. The joke was that if Johnny could hit a dance step, he’d be in the group. Seems he never did, but they let him in anyway. “Johnny came in singin’. I could hit a note here and there, but that nigga wasn’t play’,” says Ricky. “Boy, when we got to rehearsals and saw that nigga dance, though—Whoooo.”

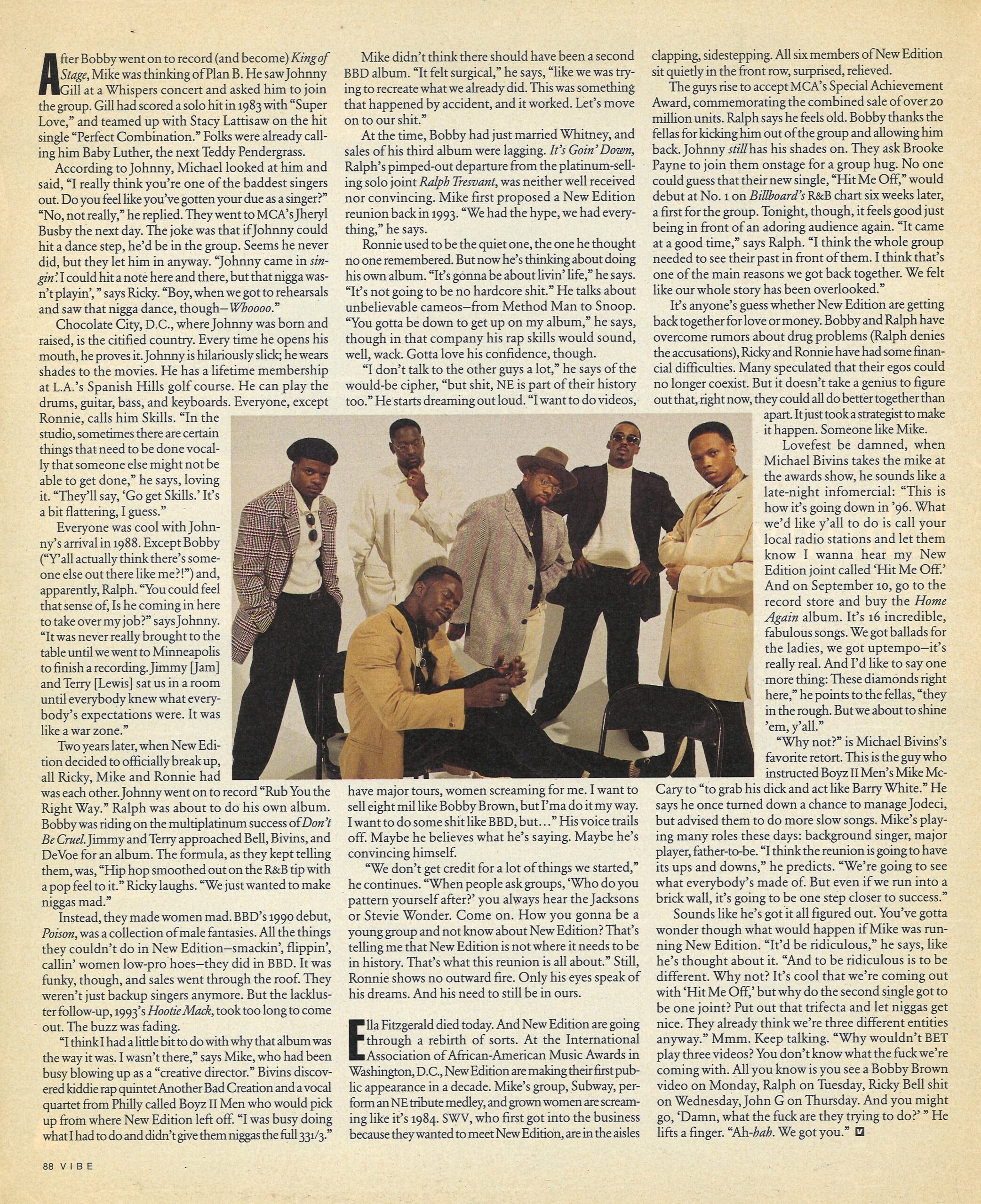

Chocolate city, D.C., where Johnny was born and raised, is the citified country. Every time he opens his mouth, he proves it. Johnny is hilariously slick; he wears shades to the movies. He has a lifetime membership at L.A.’s Spanish Hills golf course. He can play the drums, guitar, bass, and keyboards. Everyone, except Ronnie, calls him Skills. “In the studio, sometimes there are certain things that need to be done vocally that someone else might not be able to get done,” he says, loving it. “They’ll say, ‘Go get Skills.’ It’s a bit flattering, I guess.”

Everyone was cool with Johnny’s arrival in 1988. Except Bobby (“Y’all actually think there’s someone else out there like me?!”) and, apparently, Ralph. “You could feel that sense of, is he coming in here to take over my job?” says Johnny. “It was never really brought to the table until we went to Minneapolis to finish a recording. Jimmy [Jam] and Terry [Lewis] sat us in a room until everybody knew what everybody’s expectations were. It was like a war zone.”

Two years later, when New Edition decided to officially break up, all Ricky, Mike and Ronnie had was each other. Johnny went on to record “Rub You the Right Way.” Ralph was about to do his own album. Bobby was riding on the multiplatinum success of Don’t be Cruel. Jimmy and Terry approached Bell, Bivins, and DeVoe for an album. The formula, as they kept telling them was, “Hip hop smoothed out on the R&B tip with a pop feel to it.” Ricky laughs. “We just wanted to make niggas mad.”

Instead, they made women mad. BBD’s 1990 debut, Poison, was a collection of male fantasies. All the things they couldn’t do in New Edition—smackin’, flippin’, callin’ women low-pro hoes—they did in BBD. It was funky, though, and sales went through the roof. They weren’t just backup singers anymore. But the lackluster follow-up, 1993’s Hootie Mack, took too long to come out. The buzz was fading.

“I think I had a little bit to do with why that album was the way it was. I wasn’t there.” Says Mike, who had been busy blowing up as a “creative director.” Bivins discovered kiddie rap quintet Another Bad Creation and a vocal quartet from Philly called Boyz II Men, who would pick up from where New Edition left off. “I was busy doing what I had to do and didn’t give them niggas the full 33 1/3.”

Mike didn’t think there should have been a second BBD album. “It felt surgical,” he says, “like we was trying to recreate what we already did. This was something that happened by accident, and it worked. Let’s move on to our shit.”

At the time, Bobby had just married Whitney, and sales of his third album were lagging. It’s Goin’ Down, Ralph’s pimped-out departure from the platinum-selling solo joint, Ralph Tresvant, was neither well received nor convincing. Mike first proposed a New Edition reunion back in 1993. “We had the hype, we had everything,” he says.

Ronnie used to be the quiet one; the one he thought no one remembered. But now he’s thinking about doing his own album. “It’s gonna be ’bout livin’ life,” he says. “It’s not going to be no hardcore shit.” He talks about unbelievable cameos—from Method Man to Snoop. “You gotta be down to get up on my album,” he says, though in that company his rap skills would sound, well, wack. Gotta love his confidence, though.

“I don’t talk to the other guys a lot,” he says of the would-be cipher, “but shit, NE is part of their history too.” He started dreaming out loud. “I want to do videos, have major tours, women screaming for me. I want to sell eight mil like Bobby Brown, but I’ma do it my way. I want to do some shit like BBD, but…” His voice trails off. Maybe he believes what he’s saying. Maybe he’s convincing himself.

“We don’t get credit for a lot of things we started,” he continues. “When people ask groups, ‘Who do you pattern yourself after?’ you always hear the Jacksons or Stevie Wonder. Come on. How you gonna be a young group and not know about New Edition? That’s telling me that New Edition is not where it needs to be in history. That’s what this reunion is all about.” Still, Ronnie shows an outward fire. Only his eyes speak of his dreams. And his need to still be in ours.

Ella Fitzgerald died today. And New Edition are going through a rebirth of sorts. At the International Association of African-American Music Awards in Washington, D.C., New Edition are making their first public appearance in a decade. Mike’s group, Subway, perform an NE tribute medley, and grown women are screaming like it’s 1984. SWV, who first got into the business because they wanted to meet New Edition, are in the aisles clapping, sidestepping. All six members of New Edition sit quietly in the front row, surprised, relieved.

The guys rise to accept MCA’s Special Achievement Award, commemorating the combined sale of over 20 million units. Ralph says he feels old. Bobby thanks the fellas for kicking him out of the group and allowing him back. Johnny still has his shades on. They ask Brooke Payne to join them onstage for a group hug. No one could guess that their new single, “Hit Me Off,” would debut at No. 1 on Billboard’s R&B chart six weeks later, a first for the group. Tonight, though, it feels good just being in front of an adoring audience again. “It came at a good time,” says Ralph. “I think the whole group needed to see their past in front of them. I think that’s one of the main reasons we got back together. We felt like our whole story has been overlooked.”

It’s anyone’s guess whether New Edition are getting back together for love or money. Bobby and Ralph have overcome rumors about drug problems (Ralph denies the accusations), Ricky and Ronnie have had some financial difficulties. Many speculated that their egos could no longer coexist. But it doesn’t take a genius to figure that out, right now, they could all do better together than apart. It just took a strategist to make it happen. Someone like Mike.

Lovefest be damned, when Michael Bivins takes the mike at the awards show, he sounds like a late-night infomercial: “This is how it’s going down in ’96. What we’d like y’all to do is call your local radio stations and let them know I wanna hear my New Edition joint called ‘Hit Me Off.’ And on September 10, go to the record store and buy the Home Again album. It’s 16 incredible, fabulous songs. We got ballads for the ladies, we got up-tempo—it’s really real. And I’d like to say one more thing: These diamonds right here,” he points to the fellas, “they in the rough. But we about to shine ‘em, y’all.”

“Why not?” is Michael Bivins’s favorite retort. This is the guy who instructed Boyz II Men’s Mike McCary to “grab his dick and act like Barry White.” He says he once turned down a chance to manage Jodeci, but advised them to do more slow songs. Mike’s playing many roles these days: background singer, major player, father-to-be, “I think the reunion is going to have its ups and downs,” he predicts. “We’re going to see what everybody’s made of. But even if we run into a brick wall, it’s going to be one step closer to success.”

Sounds like he’s got it all figured out. You’ve gotta wonder though what would happen if Mike was running New Edition. “It’d be ridiculous,” he says, like he’s thought about it. “And to be ridiculous is to be different. Why not? It’s cool that we’re coming out with ‘Hit Me Off,’ but why do the second single go to be one joint? Put out that trifecta and let niggas get nice. They already think we’re three different entities anyway.” Mmm. Keep talking. “Why wouldn’t BET play three videos? You don’t know what the fuck we’re coming with. All you know is you see a Bobby Brown video on Monday, Ralph on Tuesday, Ricky Bell shit on Wednesday, John G on Thursday. And you might go, ‘Damn, what the fuck are they trying to do?’” He lifts a finger. “Ah-hah. We got you.”